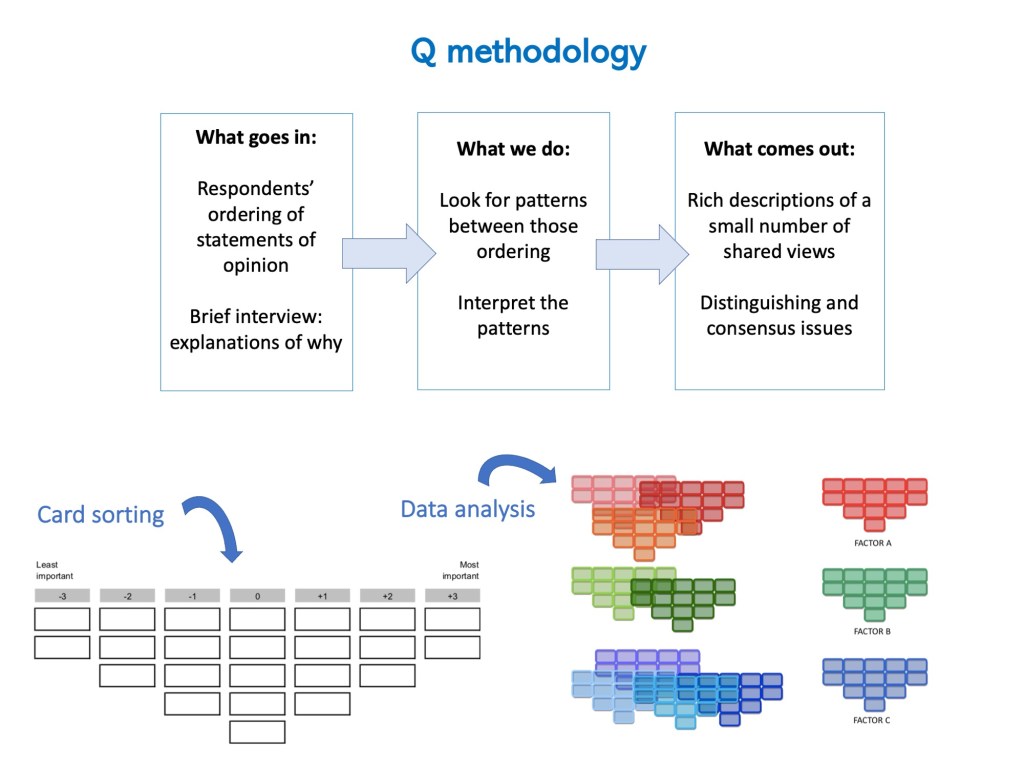

Q methodology combines qualitative and quantitative techniques to study subjectivity. Using Q techniques, researchers are able to uncover and interpret shared views, perspectives, opinions, values, and beliefs (Brown, 1996). It provides a systematic and rigorous method for examining human subjectivity that helps identify and understand similarities and differences in individual positions through their ranking of a set of fixed statements (Addams & Proops, 2000; Brown, 1996; Dasgupta & Vira, 2005; Ramlo, 2016).

In April 2024, Silvia Futada (PhD student, SNRE) and I organized a workshop on Q methodology, where participants learned from the experiences of three UF researchers applying it in their doctoral projects: Dr. Sinomar Fonseca (SNRE), Dr. Felipe Veluk Gutierrez (SFFGS), and myself. Dr. Fonseca utilized Q methodology to assess local stakeholder perspectives regarding the free, prior, and informed consent processes related to significant infrastructure projects. Dr. Veluk employed this approach to gauge stakeholder attitudes towards Amazonian nut community-based initiatives and bioeconomy. Both Sinomar and Felipe conducted their research in the Brazilian Amazon. My research, on the other hand, utilized Q methodology to engage local stakeholders, including small-scale farmers, in discussions concerning the role of fire and its effective management in the Peruvian Andes.

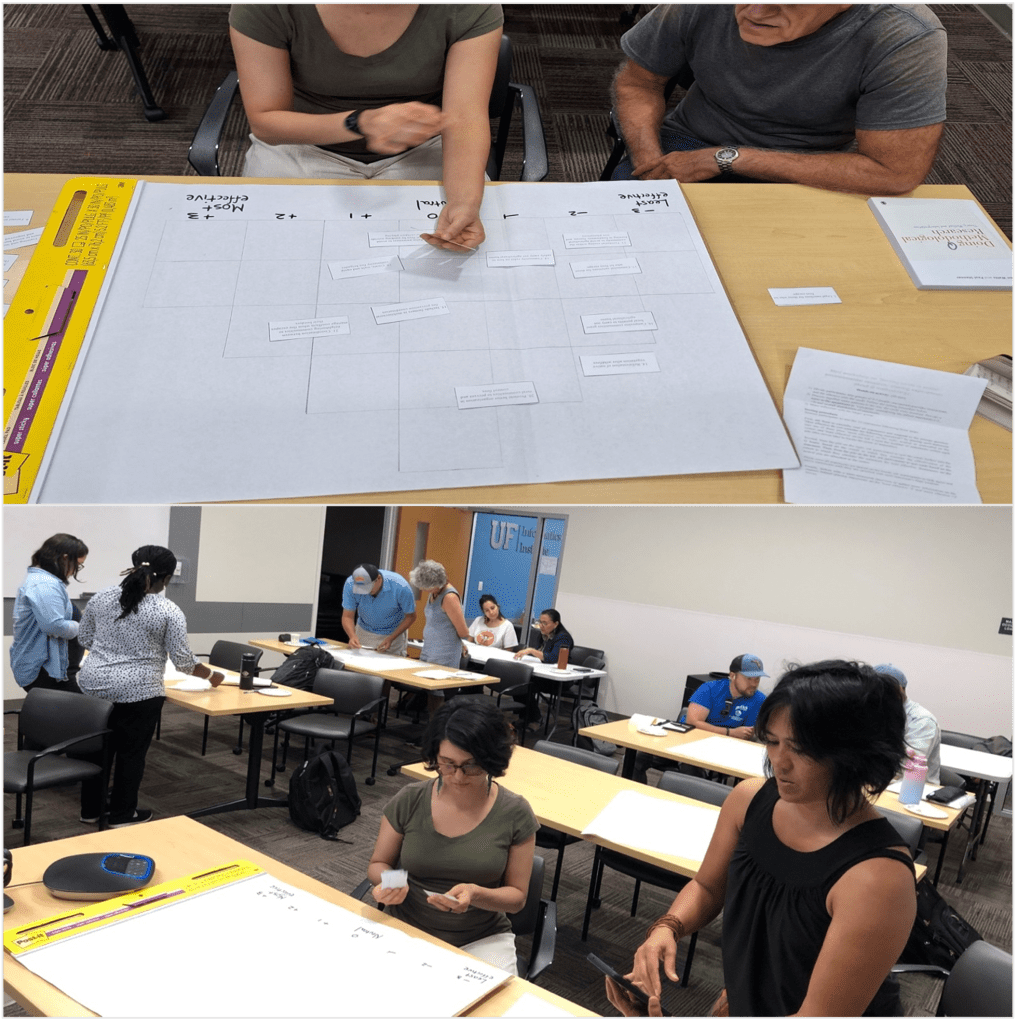

Workshop participants sorting cards in a Q sort structure

During the workshop, we requested participants to form pairs and practice data collection of this method. One person gave instructions while the other sorted 23 statements (or actions) related to fire management -the same one I used in my doctoral research- into a grid. Participants acting as respondents sorted the statements in two stages. The first stage involved arranging the statements in three piles, considering the level of effectivity of each statement: most effective, least effective, and neutral. Next came the actual sorting, in which respondents considered how strongly they felt about each statement. They placed each one along a response grid or Q sort structure provided in the workshop. The Q sort resembled a normal distribution or bell curve, with most statements placed in the middle or neutral area and fewer at the extremes. Since respondents ranked statements relative to each other, they adhered to the prescribed Q sort structure when arranging the statements. The resulting Q sort or grid arrangement was entirely subjective, reflecting the respondent’s individual views or opinions.

Further data analysis involves correlation and factor analysis, with each Q sort serving as the unit of analysis. Unlike other methodologies that compare group responses, Q methodology assesses all collected Q sorts against each other. Pattern analysis identifies similar Q sorts, forming clusters representing shared views or subjectivity, leading to the emergence of factors representing commonly held viewpoints. Factor analysis then generates composite Q sorts for each factor, providing a representative arrangement of statements. These composite Q sorts, coupled with transcripts of participant interviews, yield detailed explanations of shared viewpoints. The process is reductive, beginning with numerous viewpoints and culminating in a concise selection of key perspectives. In the end, Q methodology does not provide generalizable results to an entire population because it relies on purposeful samples, but it does give an approximation of the diversity of viewpoints existing in a particular set of key actors.

Data collection with Q methodology in the Peruvian Andes

In my research on fire management, I conducted Q methodology with 56 stakeholders, including members of Quechua communities, firefighters, researchers, nonprofit organizations, protected areas, and government agents. Factor analysis revealed three distinct viewpoints on the role of fire, ranging from emphasizing the negative impacts of fire on ecosystem services (e.g., on biodiversity and climate change impacts) to acknowledging some of the benefits of fire for rural wellbeing (e.g., that agricultural burns open new farmland or fire as the most accessible way to work the farm). My research also found three viewpoints on effective fire management: top-down fire suppression, community-based fire suppression, and community-based fire management. Most government agents and firefighters, holding an emphasis on the negative impacts of escaped fires, advocated for the continuation of top-down fire suppression policies, whereas community members and other external actors with a more balanced perception of fire advocated for community-based actions, either suppression or management. Q methodology served as a tool to reflect on the need for fire governance in the Peruvian Andes that reconciles the different needs of various stakeholders, especially those of frontline fire users.

Literature cited

Addams, H., & Proops, J. L. (2000). Social discourse and environmental policy: an application of Q methodology (Vol. 16). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Brown, S. R. (1996). Q Methodology and Qualitative Research. Qualitative health research, 6(4), 561-567. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239600600408

Dasgupta, P., & Vira, B. (2005). Q methodology for mapping stakeholder perceptions in participatory forest management. Annex B3 of the Final Technical Report of project, 8280.

Ramlo, S. (2016). Mixed Method Lessons Learned From 80 Years of Q Methodology. Journal of mixed methods research, 10(1), 28-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815610998